Dec 23, 2025

By Harpreet Ahuja

My deepest thanks go to Diego Salazar Lira for his guidance on the writing and the interview stages.

DISCLAIMER: Sharing vulnerable truths about race and privilege in an intimate relationship can invite misunderstanding. Please read this with an open mind toward the concepts and with an understanding of the vulnerability required to put these complicated truths to the page.

Privacy and consent: My partner has given me his consent to use our story and publish this post. Together, we brainstormed the challenges in our relationship which are reflected here. I also have permission from the contributors to share their stories. To protect privacy, all names have been changed.

The hidden labour of interracial love

Love, when inhabited by someone who is racialized, is full of additional considerations, especially when it is a mixed-identity relationship. To explore the complex nuances — the hidden costs, the unexpected shields of privilege, and the opportunities for growth — I share my own story alongside the intimate, candid interviews of four other individuals. Their testimonies offer a crucial look at the pressures baked into these partnerships, exposing a landscape where education is a prerequisite for connection, and where partners must constantly negotiate the tension between their identities and external perceptions.

Learning is a prerequisite for love

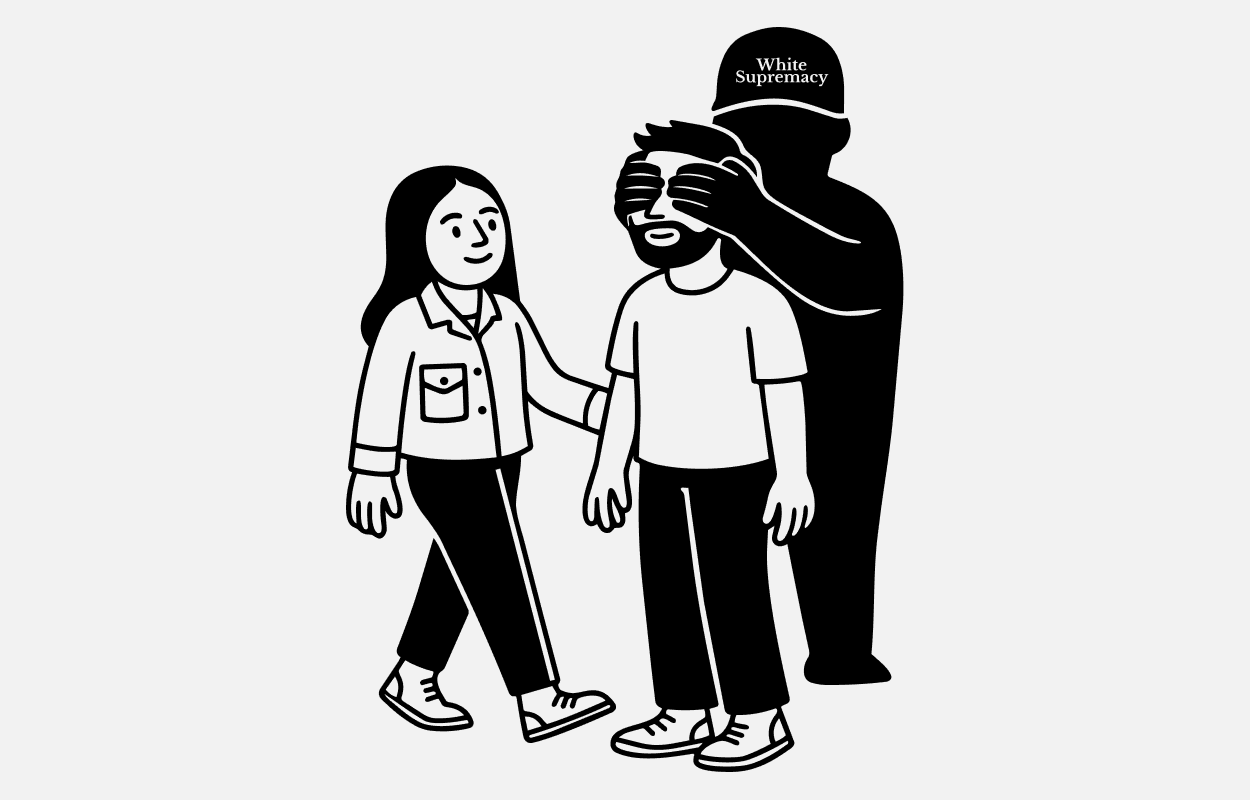

The distance between how Marc and I have moved through the world — and how we consequently see the world — is vast. I live and breathe the subject of racism. I have early childhood memories of being the recipient of racism, which led me to spend my career trying to understand, navigate, and challenge racial oppression. Since I am the first non-white person he has dated, Marc, my white partner, has only recently begun to confront his own blind spots. This gap is where the labour of our interracial relationship resides.

I am often emotionally depleted trying to satisfy his “burden of proof,” providing evidence and rational explanations for realities that are simply facts of my life. I also find myself managing Marc’s emotional reactions — including defensiveness and guilt — when we engage in the power dynamics of race, all while simultaneously processing my own experiences of racism.

While my labour mostly involves bridging the gap between Marc’s blind spots and my reality, for others, the hidden labour manifests as navigating a partner’s prejudiced family, struggling against internalized narratives, or the exhausting effort of making their lived experiences “palatable” for those they love.

Maya and Tim: Confronting the family

For some, the labour extends beyond the partner to the environment that raised them. Maya has felt this deeply while dating Tim, a white American citizen. As a Mexican woman in California, she often finds herself navigating the traditional, conservative world that shaped him.

She describes her partner’s family as blue-collar workers who are proud to be white, holding a “strong and imposing view that they are the best people in the best country.” She describes Tim’s family as trying to be nice to her while vocalizing racial biases. This was clear when, for example, his father told her, “I didn’t think someone like you could speak this level of English” — an insult framed as a compliment.

For Maya, the struggle isn’t just with her partner, but with his “immediate circle,” which constantly pulls him back toward his normalized, white-centric environment.

She shares how things started to change the moment Tim finally confronted his father:

“At first, I felt I should keep my mouth shut because Tim told me you are not going to change a man in his 70s. But the moment Tim confronted his father, he gave me the space to communicate how I see the world and how I think; this has been useful.”

Elias and Antonio: Internalized othering

Elias was born and raised in Mexico, while Antonio is an American citizen whose parents immigrated to California from Mexico. Despite their shared cultural background, the way they inhabit their Mexican identity is profoundly different. Elias recognized that Antonio’s views about “being Mexican” were grounded in harmful stereotypes. Specifically, Antonio viewed all Mexicans as poor and struggled to reconcile Elias’s middle-class status with his claim to Mexican identity.

Stereotypes can become deeply ingrained in a person’s self-concept, especially when their national identity is forced into a subordinate position by hegemonic culture. Elias shared the negative impact of these stereotypes on his self-esteem, stating:

“There is a tendency to think that Mexicans are on the hunt for a relationship that secures them immigration status. I constantly find myself having to bring ‘evidence’ that I am worthy of love and the relationship, either through my education, intellect, or sense of humour. As a brown Mexican, I do not satisfy white standards of beauty, so I have never been fearless on the grounds of my physical appearance; I have been fearful. My self-esteem has been deeply impacted by narratives that oppress who I am and where I come from.”

Luis and Bharat: Making racism palatable

Luis, who is from Mexico, met his partner Bharat while studying at Yale University in Connecticut. Luis explains that he conceptualizes privilege differently than Bharat, who was born in the United States to parents who immigrated from India. Luis views privilege as more encompassing, including the power dynamics of race, which often forces him to sacrifice his own comfort to protect his partner’s feelings during conversations.

He learned early on that he needed to be more patient and educate his partner on systemic racism, often finding himself in a difficult position where challenging their assumptions felt like a threat to the harmony of the relationship.

One experience that stood out for him was when Bharat proclaimed that “people migrate to the United States because it is the best country in the world.” As Luis described, “When Bharat succumbs to these kinds of post-colonial oppressive narratives, I used to shut down because I didn’t know how to deal with it. But I learned over time that it might be necessary to be a bit pushy because I am not exaggerating about the negative impact.”

Worried about addressing the impact of his partner’s statement head-on, Luis offered this observation:

“We mold ourselves to make sure we are palatable. How do I put it so I don’t hurt your feelings, meanwhile I am the one that is hurt?”

Benefiting from the structures you fight

While Luis describes the exhausting work of making his pain palatable for the sake of harmony, there is an equally messy complexity in the moments where that same systemic power works in our favour. As we consciously decide to build a family, I have had to reconcile my fight against racial hierarchy with the reality that I benefit from Marc’s white privilege.

With Marc, we have the means to buy a home, and I have the time to pursue artistic freedom that might otherwise be out of reach. In public, I often let Marc take the lead, knowing that his voice carries a weight mine does not. It is this messy complexity that has ultimately forced us both toward growth.

My relationship with Marc has motivated me to cultivate patience and find a steady confidence that I didn’t have before. I have become more skillful at discussing covert racism, where I don’t immediately have the words to describe the experiences that unfolded before me. Witnessing Marc struggle as he tries to make sense of my lived experience has expanded the parameters of my empathy.

Maryan and Bogdan: The face and the name

Maryan’s start of her relationship with Bogdan marked a significant shift, as he is the first white person she has dated. As a proud Black woman of Somali and Muslim heritage, whose family settled in Toronto when she was four, she never envisioned herself being with a white man. Having grown up in the multicultural mosaic of Toronto, she always assumed she would ultimately partner with someone who shared a distinct ethnic background, feeling that a “typical Canadian” white man would not align with her identity. However, Bogdan proved to be an exception.

While he looks white and is therefore seen as white, Bogdan identifies strongly with his distinct Serbian background. He is a second-generation Canadian-Serbian and does not identify as a white person.

While Bogdan may not identify as white, Maryan is acutely aware of the social shield his appearance provides, noting specifically how she and their children benefit from the way others perceive him:

“The parents at my children’s school might not know my children’s ethnicity because of their own assumptions about biracial identity. I’ve noticed that once they find out their father is white, they behave differently. They immediately behave better around me and my kids and become more careful about what they say.”

However, Maryan notes that his “social shield” has a distinct limit, explaining that while Bogdan looks white, his ethnic name serves as a “giveaway” that shifts how others perceive him:

“We have a dynamic where I benefit from his white privilege, and he understands that better than most because he is only considered white until you hear his name; when his name is called out, this is a giveaway.”

Love, anger, and the path to growth

Inherent in my relationship is a constant contradiction. On one hand, there is the overwhelming excitement to build a family, to raise our little girl, and to finally break free of generational trauma. On the other, there is tension rooted in white fragility that translates into a cycle of inaction. I feel a profound love for Marc, yet I often carry an exasperating frustration toward the pace at which the needle moves forward for our family.

This friction is the “hidden labour” that Maya, Elias, Luis, and Maryan know so well. It is the resilience required to withstand a partner’s prejudiced family, the exhausting work of being believed, the sacrifice of making one’s pain “palatable,” and the dizzying effort of navigating a world that grants privilege to a face but not a name. Whether we are teaching a partner to see systemic racism or learning to navigate the social shields their presence provides, we are all operating in a landscape where love requires a relentless kind of education.

We naturally tend to gravitate toward romantic partners who look and feel familiar. Marc made a conscious decision to love and commit to a racialized person, knowing the path would not be easy. Our journey together has been bumpy, requiring us to navigate the vastly different lenses through which we see the world. But through the testimonies of others and our own shared struggles, we have challenged the limitations of sameness.

Ultimately, we have found that connection, not familiarity, is the most powerful catalyst for growth.

Meet Harpreet: Harpreet Ahuja is a lawyer, human rights consultant, and social justice advocate driven by the conviction that systems need reimagining. Her work explores the intersection of law, policy, and lived experience—and tells the human stories behind injustice. Harpreet is based in Vancouver on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations, and publishes on her website.